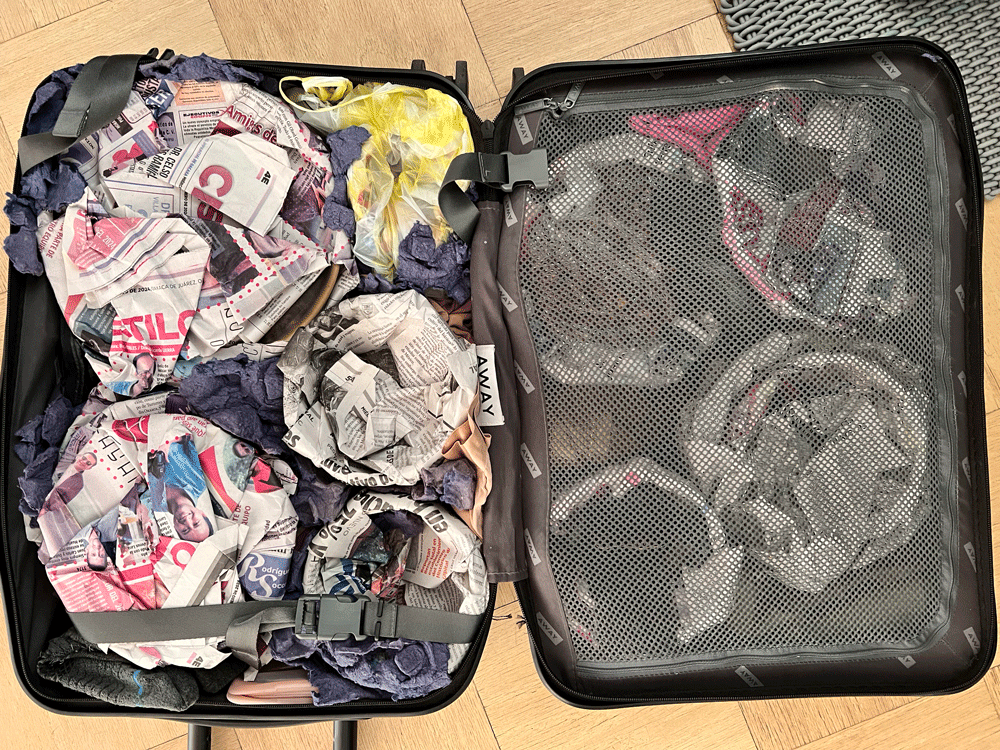

This past week, I tried something novel: I planned a solo trip, not for work, not on assignment, but just to fall back in love with humanity. Seeking out new/old culinary practices and trolling local markets makes me a better cook. It’s the spark of inspiration for so many of the recipes I have created over the years, but most importantly, travel is a much-needed counterpoint to life in relatively sleepy Pasadena, where the same people pass by my window like clockwork day after day. I feel the most secure in my life choices when I find I’m enjoying a local variation on chicken soup in a place whose texture I never could have conjured on my own, and then again when I return to my family and unpack my suitcase of smuggled beans, spices, honey and ceramics.

For some time, I have been aching to go to Oaxaca to visit my dear friend and frequent collaborator, Niki Nakazwa. Niki has opened doors for me in Mexico I never could have imagined, and I have been profoundly changed by the access she has given me to that culture over the last ten years. We stayed up all night with a roadside vendor stirring a caldron of carnitas, we served grilled frogs’ legs at a pop-up in Mexico City, and ate an astounding portion of uni for breakfast at the home of Mexico’s premier seafood distributor. (Those are the wins. We also bought prescription-grade retinol in Ensenada and nearly burned our faces off in a naive attempt at a grown up skincare routine, well before skincare was my low-key passion).

When Niki was in L.A last, we collaborated on a food and mezcal pairing (she will be back in April, if Angelenos want to book us for an event). As we prepped, she told me about a collective of women in a small Oaxaca town, dedicated to the art of making pulque. They call themselves Organización de Mujeres Milenarias. I am wild for pulque, a low-alcohol indigenous beverage whose origins date back thousands of years. The refreshing probiotic drink is made from the agua miel extracted from the agave plant, lightly fermented to an effervescent tang. I had been jockeying to write about this remote collective, but after hours of research, writing the pitches, and countless shunted email exchanges, I had no takers. The travel pubs that are still in business favor itineraries that an average tourist might replicate (more clicks). I couldn’t sell the story. I decided to go anyway.

The morning after I arrive in Oaxaca City, Niki picks me up at my hotel late. She had just been shaken down by a cop for $200 after purportedly making an illegal turn (we still have no idea if she broke any rules, since the traffic lights and signage in Oaxaca are written in Morse code). Once out of the city, the route is harrowing -- drivers pass one another at aggressive turns with zero visibility, except for the ominous drop into the gorge below. Exiting the highway, the roads are prone to dead-end into 20’ high piles of rubble. Google maps implodes.

We are an hour late to meet the women of the collective, but we stop to pick up two elderly women hitchhikers. We take them to their church to gather food and drink for their neighbors who are engaged in regular Sunday service, tequio. In the absence of governmental aid, villages self-organize to repair infrastructure, and these ladies were essentially the highest form of craft service. When we refused their money for the ride, they reached into a bucket and handed me a chile relleno snuggled inside of an oversized tortilla made from a blend of native wheat and corn (this is the dominant tortilla style in Oaxaca). It was priceless and well received.

Finally we arrive at the pulque collective and the women are waiting for us, weaving palmas to make mats and baskets while standing in the high-noon sun. We follow them up the hill of rust colored earth to their cinder block home. They feed us a soup of broken corn and fava beans before heading to the maguey for their midday service.

We watch as one of the women removes a boulder covering a cavity in the center of the dinosaur plant. She uses a wide spoon to scrape the heart of the agave, stimulating the agua miel to weep and pool. Using a recycled coke bottle fixed with a wide plastic straw, she sucks the syrup up like a hummingbird and transfers it into a clay pitcher. She replaces the rock and we move on to the next plant. Each agave will produce agua miel for as long as 6 months if it is scraped three times a day (the echoes of lactation abound).

The taste of fresh agua miel is reminiscent of sugar cane juice. Its sweetness surprises me, even though I am well aware that agave syrup comes from the same plant. It’s incredible to think a plant could hold such richness in the midst of this harsh landscape. Once back at the house, the ladies add the fresh agua miel to a mother culture of living pulque. The agua miel freshens up the older stuff that has already begun to ferment, and the existing bacterial cultures go to town metabolizing the newly introduced sugars. We sit on hand carved stools and each receive a jicara filled to the brim with foamy, opalescent pulque. No doubt there’s some placebo effect here, but I feel like every cell in my body is hydrated instantly. The pulque, no longer heavy with residual sugar, has developed a mellow acidity, like kefir, but with a smooth and velvety mouthfeel.

Pulque was once a staple across Mexico. Even after the Spanish conquest, pulque production was a source of great wealth for mestizo families. But in the 18th century the Spanish poured resources into imports of brandy and wine, diminishing the population’s appetite for indigenous drinks. By the 70’s, the Mexican government capped the price of pulque in the marketplace. They pushed industrialized beverages, namely, soda, and characterized pulque as a backwards, unsophisticated practice. There was money to be made and international trade deals to seal, and it came at a cost to indigenous customs, particularly those that defied any and all efforts towards commodification.

Pulque cannot be bottled and sold; as mezcal, tequila, and even tepache have been exported abroad, pulque stands its ground as highly ceremonial and site-specific. Its essence is anti-capitalist and it cannot be contained. Without constant attention, a sealed bottle would over-ferment and explode. Time-based, in a constant state of flux, a pulque today will be unrecognizable tomorrow. The longer it ferments, the boozier it becomes, and the texture changes from suave to goopy. If you’re saving it for tomorrow, you’re missing the point. Pulque is about the NOW.

Driving away I cradle a liter Coke bottle of bubbly brew that I have committed to “burping” for the next 12 hours to prevent an accidental pipe bomb. Because I had pitched this experience to travel magazines, I could feel myself writing the piece in the moment, taking notes and photos like it was a job. I want so badly to write about this experience. I wonder what I will do with the photos I took? Instagram is too flip a medium for something like this. I recall my dear friend, Stephanie Danler’s, urgings before I left, and I decided to start a Substack.

So much for “not working.”

Want my guide to eating, drinking, and custom ceramics? Upgrade to paid.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Salad for President Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.